There is No Real Country Music

Remembering the Past, Creating the Future and Saving Country Music

After the pioneers of neo-traditional country music hit radio waves in the late 1980s and proved themselves commercially viable, a tidal wave of “Hat Acts” emerged, known more for their tight jeans, rock ‘n’ roll flare and big cowboy hats than chords and truth. And many traditional country musicians did not hold back: They did not like these guys. In fact, many hated what they represented.

Some of the biggest names in traditional country music dismissed these artists for performing without heart. These newcomers lacked the all-important and ever-elusive authenticity, the greats would tell pretty much anyone who’d listen. Nearly the entire prologue of In the Country of Country, the oral history of major “real” country musicians by Nicholas Dawidoff published in this period, is filled with these critiques.1

Today, there has been a resurgence of that late 80s and early 90s neo-traditional sound, which allegedly will save country music for the next generation.

In a recent Saddle Mountain Post article, I discuss the rise of this neo-neo-traditional country music. The piece explores the power of nostalgia and a misremembered past, which allows people to believe whatever they want about what came before them.

Rob Harvilla, host of the podcast 60 Songs that Explain the 90s and author of the book of the same name, closed our interview for that article noting:

“It’s the passage of time and the realization that all these genres, all these sub-genres, and all these walls that allegedly exist between all this music are all a lot more porous than you think. From our safe perch here in 2024, we are free to recreate our own 90s and decide what that means and what that sounds like.”

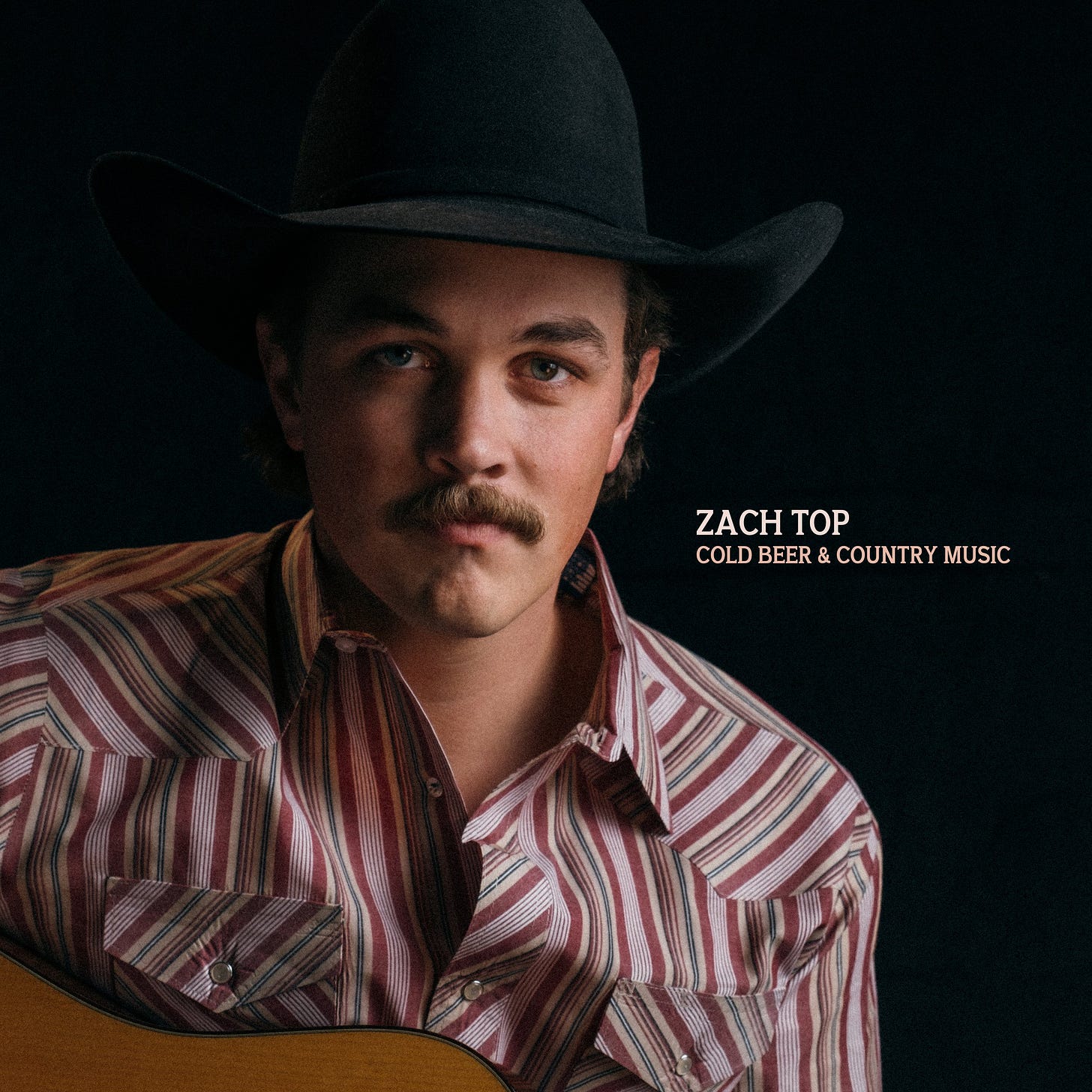

The reason I started exploring this topic was 100% due to the meteoric rise of Zach Top throughout 2024. From his first major single, “Sounds Like the Radio,” to his biggest hit to date, “I Never Lie,” Top has used nearly identical production methods, similar lyric structures and the same themes as many of the biggest Hat Acts (and those who were more respected) from the early 1990s.

From Saving Country Music to Nikki in Nashville to Rolling Stone, Top dominated the 2024 year-end best-of lists. For good reasons: his album sounds great, his live shows fill every larger venue with incredible energy, and his guitar chops are undeniable due to his bluegrass upbringing. His sound straddles the George Strait early years and some of the poppier later years of the neo-traditional revival.

In fact, he provides a near facsimile of what was heard on the radio in the early to mid-1990s. This includes a lack of updated references that I find detract from the experience.

In “Cold Beer & Country Music,” he sings about how he needs to sit in a bar and have a few cold ones to feel better. Now, that is a pretty country idea for a song. But these lines don’t belong in the mid-2020s:

Hey bartender, I need me one of those long necks

Yeah, man, that's good, about as good as it gets

Here's a 20 for the jukebox, crank it up, please

Here's another 50, run a tab for me

No one is running a tab on cash, and the jukebox is operated via smartphone.

These lines distracted me from listening to the song. I suppose the inflated cost of the music and beer could have snapped me out of it. But beyond that, these lyrics feel forced and heartless.

I’m left asking how something that was once seen as the antithesis of country music — something lacking authenticity due to its lack of heart — can save the genre from its modern-day equivalent. Yesterday’s Hat Acts are today’s BroCountry bros.

This is where history — or history as we remember it today — comes to life.

The Misremembered Past

Top and many others are using music that was popular before they were born to reinforce their place within country music. And this shouldn’t surprise anyone.

More than any other genre, country music looks backward for validation. Top has been quoted in articles about his style, noting that his influences are the same traditional artists that Strait, Alan Jackson and others referenced as their influences — not the neo-traditionalists themselves. Dzaki Sukarno, a New Mexico-based country artist, told Honky Talkin’s John-Carter that he sees himself as traditional, not neo-traditional or neo-neo-traditional. Sukarno wasn’t alive during the first or second iteration of this style’s popularity.2

Maurice Halbwachs, a French philosopher and sociologist, explained that “everything seems to indicate that the past is not preserved but is reconstructed on the basis of the present.”3 He also argued that our place within a society informs how we remember our memories.

Put simply, we do not remember anything as it was but only in relation to what is today and the so-called “collective frameworks” of the people, culture and institutions surrounding us.

“Collective frameworks are...the instruments used by the collective memory to reconstruct an image of the past which is in accord, in each epoch, with the predominant thoughts of the society.”

So when country music evolves because it always does, we rely upon those “predominant thoughts of the society” to identify something within this changed product as real country music connected to the past. It usually feels like what it once was—but as it is remembered today.

“Society from time to time obligates people not just to reproduce in thought previous events of their lives, but also to touch them up, to shorten them, or to complete them so that, however convinced we are that our memories are exact, we give them a prestige that reality did not possess.”

Or as renowned philosopher and social commentator Waylon Jennings famously asked, “Are You Sure Hank Done It This Way?”

Perhaps there is no way to know how Hank, either George, or anyone else did it, as we only remember it as it is today. We allow tastemakers and critics to help us identify what was so we can understand what is, and today, in country music, the collective memory and institutions have shifted.

Many look to Strait and Jackson as examples of classic country. But they looked to Lefty Frizzell, Patsy Cline, Ray Price, Kitty Wells or Ernest Tubb for the classic country sound. And they likely looked to Hank Williams, who looked to Jimmie Rodgers and Roy Acuff, and so on.

According to Halbwachs, this is expected as there is no pure memory.

History can be studied, sources can be understood — but memory is malleable. Authenticity is found at the intersection of fact and memory.

Country Music Evolution

Recently, I had an interesting conversation with a friend about the definition of country music. He’s a musician and band leader who has worked with various artists, from classic country outfits to pop icons, on stages big and small.

He asked me how I define country music. I bumbled around a bit and gave him some bull about auxiliary strings, a bit of twang and the theme of the song. I landed on the theme being the most important.

I told him it needed to be about people, stories that go untold and yes, some “country stuff” like land, time, values and tradition. Within those themes, there is a range of expression that allows well-written, complex songs to exist alongside mass-produced MadLib-style songs that dominate radio play.

He pushed back and said, “I don’t think it can be defined anymore.”

He grounds his point with Tyler Mahan Coe's argument that country music is the only genre that has changed as much as it has and still is called what it was before those changes. The genre’s obsession with its identity as defined by its past ignores its evolution.

And, of course, it’s changed. Nothing that exists within a creative space remains unchanged over time. Perceptions, experiences and time change how people consume art — regardless of its original intention.

But does this mean there is no new country music? If so, how can we save it if it exists only in the past? This seems to be a question of preservation rather than the future of the music.

What are we saving?

When we talk about saving country music, it seems we are trying to go back in time to a period of purity and simplicity. However, there is nothing pure or simple in the evolution of country music — or any commercial art form.

The creation of modern commercial country music was not organic but rather a deliberate effort to sell a product and develop a commercially viable industry.4 In every generation, the marketing has shifted and augmented itself to fit the audience's desires while keeping the same nomenclature. Each iteration of the genre was commercialized, defined and marketed to the masses as country music.

The founders of the Outlaw Movement had no interest in being called outlaws. In a yet-to-be-released documentary about these luminaries, Jessi Colter noted that they didn’t call themselves anything but musicians.5 Jennings, Willie Nelson, Colter and the other folks involved in this space were defined by their record labels to be more easily marketed to consumers.

Defining country music has always been about selling records. And because of the audience’s (and pundits’) fascination with authenticity, the newly created product must be marketed in a way that makes people feel like it’s tied to the past. Even if it’s brand new.

Sounds Like the Radio

Zach Top created something familiar. However, Top ignores the modern influences that inform much of the newest traditional albums.

Top set out to play a memory of something brand new. A sound and style from the past as he hears it today.

And it worked.

Daidoff, Nicholas. In The Country of Country: People and Places of in American Music. Pantheon Books, 1997.

John-Carter. Honky Talkin’ (podcast) 2024.

Halbwachs, Maurice. On Collective Memory. Edited and translated by Lewis A. Coser, The University of Chicago Press, 1992.

Peterson, Richard A. Creating Country Music: Fabricating Authenticity. University of Chicago Press, 1997.

They Called Us Outlaws. Directed by Eric Geadelmann and Kelly Magelky, Shaddowbroke Studios, www.theycalledusoutlaws.com

.

Hey Country Cutler,

First off, thanks for the discussion.

However, I have to say, it's a little disappointing you have decided to have a discussion that only goes one way.

You say in this article, "When we talk about saving country music, it seems we are trying to go back in time to a period of purity and simplicity." But nobody has said that. The only person that is saying that is you, because it tees up the argument you want to make.

Instead of making assumptions of what we're talking about when we say "saving country music," why don't you just ask? I've spent the last 18 years running a website called "Saving Country Music" and published over 9,000 articles under that name. Perhaps I have some insight into it beyond you taking a surface inference from an Instagram post about Zach Top and expounding upon it because it easily fits your preconceived notions. Or, spend some more time actually reading the content of the website to the point where you could cite it as a source on your article that mentions 'saving country music' in the title. If you would have done so, you would have never distilled what I mean whenever I use the phrase 'saving country music' to, "trying to go back in time to a period of purity and simplicity."

By the way, attempts to over-intellectualize something that derives its beauty and meaning from simplicity is not only fruitless, it can be elevated to the level of being outright insulting to the art form.

If you want to know what saving country music means to me, what it means to the thousands of people who read the website every day, perhaps come to the website, poke around, send an email and ask that question.

But please, don't assume. Saving Country Music is not an Instagram account.