I was passively listening to some classic country music in the car last week when “Mr. Bojangels” came on. My nine-year-old asked what the song was about.

I paused and thought.

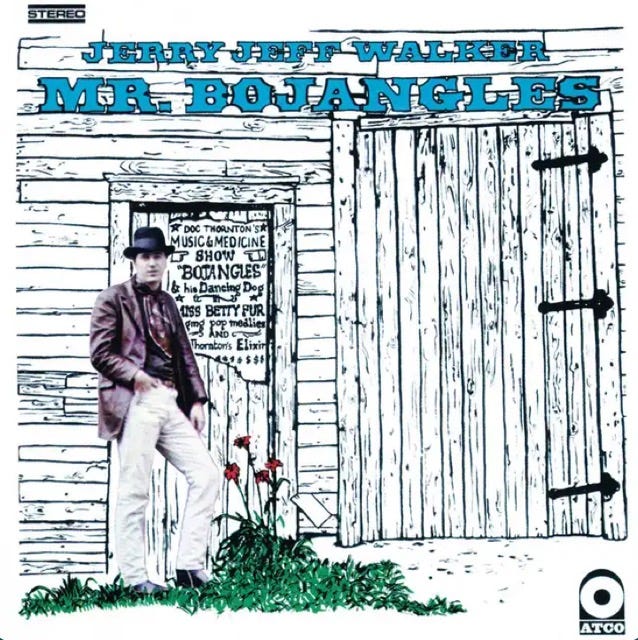

“It’s a sad song about a man,” I told him as he stared out the window, trying to listen along to Jerry Jeff Walker’s version of the song.

I could hear him thinking.

The pain of its telling and the clear sadness mixed with activities that should be joyous place the tune squarely within the American Song Book, but in the chapters we don’t like talking about regularly.

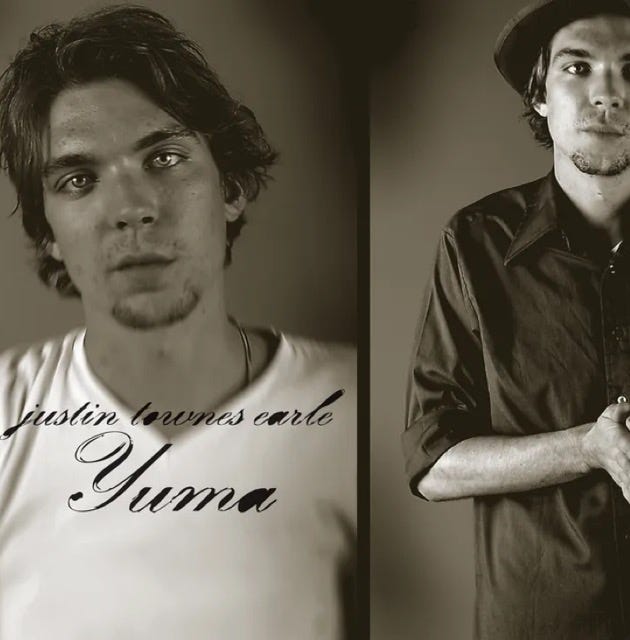

The next day, Justin Townes Earl’s “Yuma” came on a Spotify radio station based on “Mr. Bojangels.” “Yuma” is easily one of the saddest songs I’ve ever heard — and it hits much harder as a father. It’s a fear all parents don’t even know we have — failing our children so horribly that they feel they have no other choice. You are also forced to acknowledge that sometimes there is nothing a parent can do.

It’s hard to think about.

I paused to look up Justin’s passing and went down a rabbit hole of Steve Earl’s covers of his son’s songs, which always make me cry, especially “Harlem River Blues.” Back in 2010, when Justin put out this song, I felt it personally. I lived just minutes from the places in the song — there was a certain kinship I had with the protagonist for no other reason than we shared space.

The younger Earl died of fentanyl exposure in 2020, leaving behind his young child and wife. His father recorded an entire album of his songs to raise money for his boy’s family. While Steve speeds up Justin’s songs, the darkness that emanates from nearly every one of these compositions is all the more haunting when a listener considers the reason for this recording.

J.T. doesn’t include the song “Yuma.” I don’t think even the great Steve Earl could have performed that one — even if he wanted to include such a sad song.

Then I immediately listened to Luke Bell’s “Where Ya Been.”

Luke Bell came across my radar when his album dropped, well before I did my deep dive into the neo-traditional country music space. I had no idea of his back story. I just heard his music and liked it. As is the case with many passive streaming discoveries, the stuff that slows you down and forces you to take note often feels like it’s been there forever — and will always be.

Yet, in the years after he put out the record (and likely before), Bell went through it, suffering through difficult times, addiction and mental health issues. I didn’t know any of this at the time and wondered why he had yet to make it big in our little part of the music community.

His song “Where Ya Been” provides a window into his suffering, made all the more powerful after his death.

Hey, mister, in the mirror, where's my friend?

I went out on the town

And I ain't seen him since

Hey-ey, where ya been?

Getting out of the car, in a less contemplative mode, the nine-year-old said, “Just look in the mirror; he’s right there,” and slammed the door.

There is a certain danger in sad songs — some folks say they like them to feel something else or like they know someone else feels the same way. But when you’re not sure what to feel, they can lead to a place that isn’t right for you.

Pop country music is saccharine and visceral, while what so many of us call “real country” music is sad, raw and deep. Even as this widely accepted fact is easily proven false, it really doesn’t matter. Life isn’t all anything, and country music is a reflection of the variations of American life. The art form serves as a mirror — regardless of whether or not you see what is shown to you.

We want to hear experiences that we can never live in our music while still believing they are ours. This doesn’t go away with teenage angst— it just becomes less acceptable.

Finding comfort in the lived or created experiences our genre presents as truth — with three or more chords — makes the art real and elevates our lives.

It also makes our sad songs sadder — especially if you can’t understand why.

Lovely - this reminds me of desperately wanting to find a Big Star record/CD in the early 90s after a friend with great music taste told me she could never listen to them because they were way too sad. I knew I’d love them based on that alone.

Thanks for this. It’s hard to articulate the appeal of sad songs.